The Cicadas Are Coming! Fear Not, Though

go.ncsu.edu/readext?984433

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲If you’ve been listening to the news lately, I’m sure you’re aware this is a special year for our prime-number-loving insects, the periodical cicadas (Magicicada spp.). The year 2024 will see the emergence of two broods, one 13-year (XIX) and one 17-year (XIII). Since these prime numbers rarely coincide, it’s been over 200 years since both emerged at the same time!

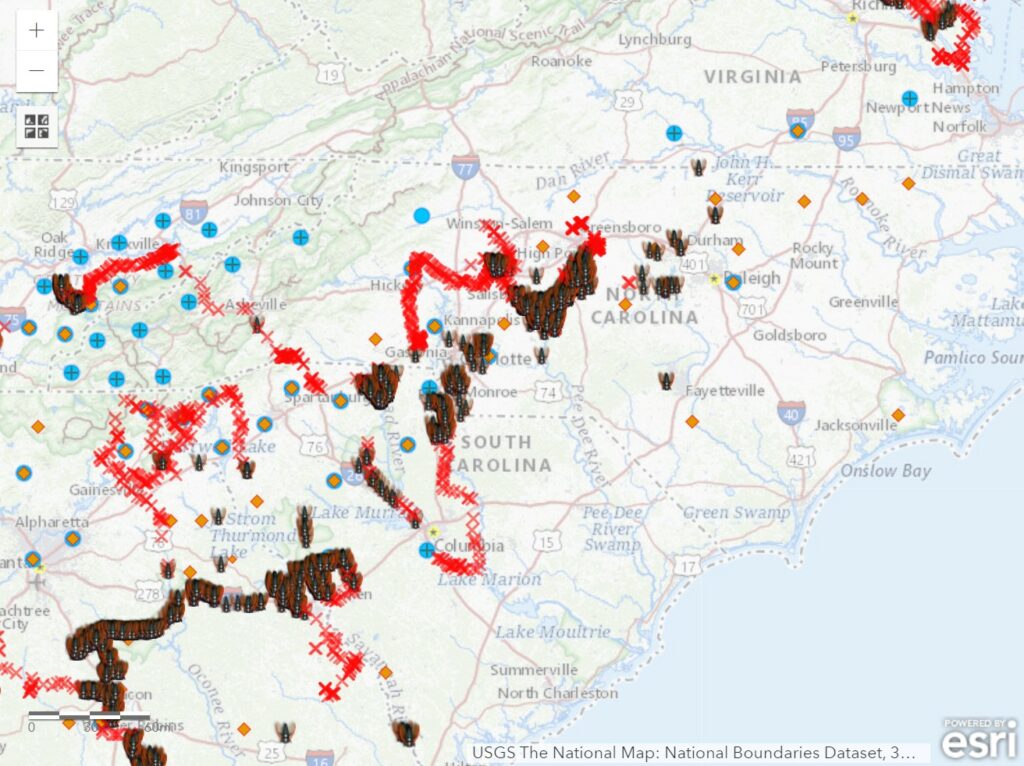

For folks living in North Carolina, only Brood XIX will be seen (the other brood is mainly in Illinois). But where they emerge they will not be hard to find: millions will be making an appearance in the west-central and western parts of the state:

Map showing records of Brood XIX in the Mid-Atlantic.

When the ground reaches a certain temperature (about 64°F, or around May in NC), the nymphs that have been underground — slowly sucking sap from tree roots — dig their way up to the surface. There they molt into an adult and the noise and mating commences.

[Side note: some people will ask “But I hear cicadas every year?” Well, unlike their periodical cousins mentioned above, the annual or dogday cicadas (large green and black cicadas, for example Neotibicen spp.) do emerge each year, nearer the middle of the summer (June/July), where they produce one of the most familiar summer sounds.]

An annual cicada, Neotibicen tibicen. These are larger, green/black species that emerge each year in the summer.

OK, back to periodical cicadas. Once they emerge, the males make a characteristic call using a tymbal organ. These calls are species specific and attract females of the same species; multiple species of periodical cicadas will emerge in this brood. These calls are deafening on their own, but when millions are “singing” it becomes a wall of sound. Once they have mated, females use their drill-like ovipositor to cut into the branches of various trees and woody plants, laying hundreds of eggs inside.

After a few weeks, the adults will die out and the young will hatch from the branches and drop to the ground below. There they burrow next to a root, and tap in for the long haul, feeding on the juices of the plant for thirteen years.

So what are people to do and how will they affect us?

The first thing to note is that in the entire world, periodical cicadas are only found in the eastern United State. So if you see them, count yourself lucky to be able to witness one of Earth’s most amazing phenomena!

Second, periodical cicadas are harmless to humans and pets. Although they may be a nuisance, this boom of insects provides many ecological benefits, especially as food for various other animals. They are nutritious and a welcome glut of food for many organisms (and even some psychedelic-producing parasitic fungi!).

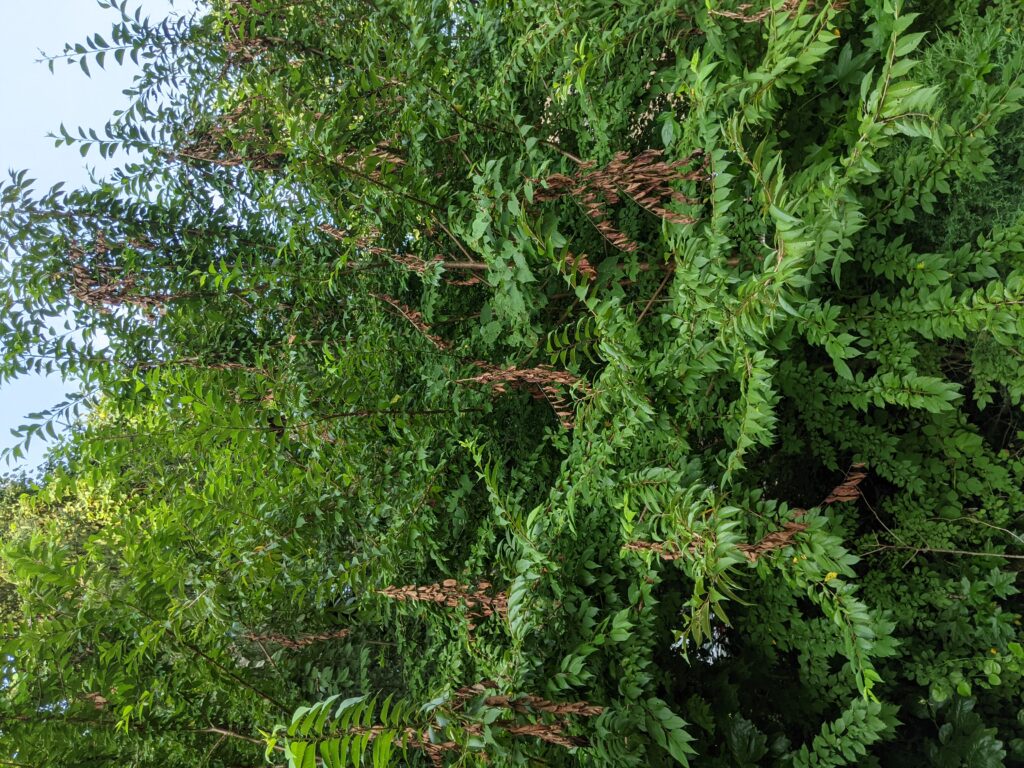

Finally, while adults and nymphs feed on plants, and females saw into twigs, they rarely do major damage and may actually improve tree health and vigor. In areas with a lot of activity, after the dust has settled, you will often notice trees and other plants with “flagging” symptoms. This is where individual branches or twigs break from being weakened by the egg laying, causing the apical section to break or die off. Unsightly as it is, this can be thought of as merely a “pruning” event, especially for mature, healthy trees. It’s even been noted that trees may flush out better the year after periodical cicadas attack them.

A large oak tree with scattered dead branch tips. This is the result of cicadas damaging twigs through egg laying.

One valid concern is that they will feed on, and lay eggs in, various woody plants, so a few commodities might be affected by massive amounts of these insects. We’ve heard that blueberry growers have seen significant damage in previous years and other woody crops (such as fruit trees — apples, peaches, and pears — as well as grapes) may be negatively affected. This is much more of a concern for younger plants as the damage may be substantial or even lethal. Luckily they are only out for a few weeks, but for growers who need advice on how to protect their plants, this fact sheet has some information.

For more information on these insects, please visit these wonderful sites: